British poet Leo Cookman considers the latest by Nigerian poet and novelist Timothy Ogene and reflects on a compelling fictional memoir exploring the history of colonization.

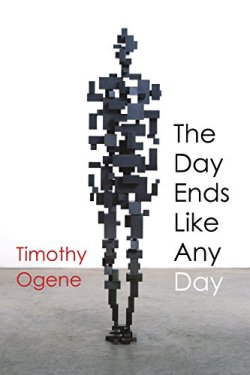

Timothy Ogene, The Day Ends Like Any Day (Holland House, 2017), 225pp.

There is a problem with diversity and representation in the arts and media, particularly in television and the publishing industry, and it is therefore refreshing to see a book not only by a writer of colour but which concerns itself with a world outside the western ‘developed’ nations. The Day Ends Like Any Day is the story of a young man, named Sam, brought up in Nigeria in the 1980s. As a painfully white subject of the most colonial of nations, this presented an immediate challenge to this reviewer, especially given that Nigeria is the only-English-speaking nation in that area of Africa and was only relatively recently (1960) made independent from British rule (which a few years later resulted in a brutal and bloody civil war). For this reason as well as many others, The Day Ends Like Any Day is an important read in a time of international quandary over issues of political solidarity such as intervention in Syria.

The long shadow of Nigeria’s colonial past in the slums outside Port Harcourt is implied throughout the text, as Sam finds a ‘real ‘education and development outside of school from a man named Pa Suku who is a product of university education and consequently someone who Sam’s domineering mother warns against. Answers to questions that are either rebuffed or outright ignored by Sam’s official carers and educators are explained with more nuance and wisdom and, importantly, without Christian influence by Pa Suku. The persecutions of a young girl made pregnant out of wedlock and the bullying of a young boy who may be homosexual are as much a result of colonial missionary work in the same way Pa Suku’s intelligent and more worldly observations are a result of the importing of British and/or classical education, to say nothing of the slums in which Sam lives being a direct result of British infrastructure and the civil war gutting certain areas and communities. This plays out further in the background of Sam’s emotional maturity in the first half of the book as well as in his relationships with his siblings – particularly his sister Ricia, his disinterested and often absent father, his school friends and even Pa Suku – relationships with whom are tested and stretched. The action relocates dramatically in the second and third parts of the book as we follow Sam through his development in University as he discovers more about his sexuality in a relationship with a man named Osagie and later with a woman called Margaret whilst he develops his own writing in the study of others.

The Day Ends Like Any Day is not described as a memoir nor as autobiographical but a read of Ogene’s short biography at the back of the book – a child born in southern Nigeria to a large family who went on to study literature at various famous institutions – gives an indication that the book may be heavily influenced by personal experience. A section in chapter three in the second part of the book clarifies the position slightly when the narrator talks about Hemmingway’s Moveable Feast as the ideal memoir: “where scenes evoke and historicize streets and faces, making them touchable”. One can only do that from real experience – it would seem – but the central conflict of the book is Sam reconciling his past life and what he hopes his future to be: he ends a relationship because of the contrast in the history of he and a partner’s life and the book closes with his worry about what dreams may reveal. Acknowledging that it can be troublesome to identify a work too closely with the biography of the author, it is nevertheless clear that the specificity of the intricate character of Sam could only be produced by a writer with in-depth knowledge and familiarity with the challenges and traumas described so vividly in the book.

The prose is, as has been commented elsewhere, highly lyrical. A result no doubt of Ogene’s origins in poetry, the descriptive sections of the book summon a sense of place and feeling with a real intensity. At the opening of one chapter Sam says “To write a memoir is to paint the past.” And you certainly get a strong image of the Nigeria of Sam’s early years. This theme of meta-commentary runs throughout the book; a book written by a Nigerian man telling the story of a young Nigerian man talking about writing his memoir. This self-reference may occasionally border on the self-indulgent but the strength of the early chapters reflects well on the later chapters that discuss the struggle of the narrator to reconcile those early experiences. Literary references are also an important part of the book and they are used with notable frequency. The regularity of both obscure and famous literary or artistic references can be rather overwhelming at times, but it also works well at others when such references are smartly woven in to the book’s narrative. For example, in the first half of the book Pa Suku introduces Sam to Dizzy Gillespie and Sam then refers to occasional faints or hallucinations in the narrative that follows as “feeling a bit Dizzy Gillespie”.

Identity is at the core of The Day Ends Like Any Day. Sam struggles with his own identity as he moves through worlds that are very different to the one he began in, in the same way Nigeria itself had to find its place not only within Africa but within modern global society after its independence. A refreshing increase in Nigerian literature in recent years – of which this is a welcome contribution – serves to remind that the similarities in individuals of any colour, creed or nation are far more pronounced than is discussed currently, as is personified in the glib phrase ‘First World Problems’ that with a hand-wave dismisses any similarity between so-called ‘developed’ Western nations and those nations that apparently fall outside this bracket.

The current trend for fierce nationalism and fear of the outsider is prevalent and pernicious across the world at this contemporary moment. In the face of this, books like The Day Ends Like Any Day point out not only the disparities between different cultures but also how we are indelibly linked to each other and that “we have far more in common than divides us”, encouraging solidarity. Identity is an ever-changing thing, a state of flux well-explored and poignantly personified in the character of Sam and with no easy answers as to how we find our own identity and, most importantly, how we accept others.

Leo Cookman is a writer living in Brighton. His poetry has been published in Poetry of Sex (Penguin Books, 2014), The Best of Manchester Poets, Black Sheep Journal, LadybeardMagazine and BlankPages Magazine, among others.

The author of The Day Ends Like Any Day, Timothy Ogene, has also previously contributed to the HKRB here.

Please support the HKRB and look out for more interviews, esssays and reviews by following our Facebook page and Twitter account.