Geoff Tibbs provides an extended review of one of the most important publications of the year, the Walter Benjamin stories.

Walter Benjamin, The Storyteller: Tales Out of Loneliness, trans. and ed. Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski (Verso, 2016) 240pp.

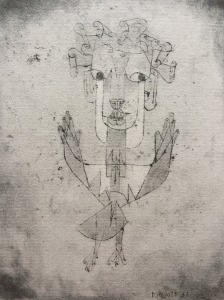

Picture the Angel of History, wings spread, blown backwards by a storm in Paradise. How wide are its wings? If you were to encounter Benjamin’s famous image in isolation, that is before seeing the monoprint by Paul Klee on which it is based, you might picture a majestic creature descending from the sky – something closer to a High Renaissance archangel than Klee.

Instead, the Angel of History, prime witness to the cataclysm of the early twentieth century, looks more like a midge caught in ointment or a misshapen seahorse than an archangel. His body is flat and weightless, mapped out with thin zigzags. His tiny, ineffectual legs seem never to have touched the ground, and his wings are raised in something like a gesture of defeat. He is a speck in the storm.

Paul Klee, Angelus Novus, 1920

There is a pointed vulnerability, almost comical, in this very unlikely figure, given the weight he is made to bear. And there is a certain unworldly tenacity in Benjamin’s choice of image – as though to indicate, in the barest terms: vertiginous insights come from unlikely sources.

The Storyteller, the new collection of Benjamin’s short fiction translated and edited by Sam Dolbear, Esther Leslie and Sebastian Truskolaski, opens with this image. It appears even before the title page, and seems to serve both as a premise and a warning. It is an early sign that this book has been carefully and tenderly assembled, setting Benjamin’s fiction in the context of his wider critical imagination. Benjamin bought Klee’s picture in 1921 and treasured it; it became, in turn, one of his own late, enigmatic images. The angel, Benjamin tells us, surveys the rubble of the past, ruins upon ruins mounting at his feet. Here he faces the rest of the book.

Each subsequent section and story is itself paired with an illustration (in a loose sense of the term) by Klee. As we read, an enduring kinship emerges between Benjamin’s prose and Klee’s wandering, mischievous line. The juxtaposition brings out a pictorial quality, not usually associated with Benjamin, in the stories: self-contained, intensely intricate and intriguing, but always, like Klee’s vignettes, internally unsettled. Benjamin, known for his mastery of the text-fragment and montage, finds an aesthetic equivalent here, not in cubist newspaper collage or surrealist photomontage, but somewhat tucked away from the modernist mainstream.

Perhaps more surprisingly still, the pairing suggests a comparable set of interpretational challenges. Klee, for Clement Greenberg, was “comfortable, musical, modest, and fantastic”: he “inhabits, really, the closed, cautious world of the modern aesthete”. Ultimately this may be no more true of Klee than it is of Benjamin. But just as Klee seems always to have to answer the charge of decoration, Benjamin’s short stories take on a number of picturesque, antiquated forms: traveller’s yarns, nursery rhymes and folk tales.

What use did Benjamin have of these forms? Are they turned to parody, or was he aiming, as the editors ask, “to reactivate the orality of storytelling under new conditions?”

The quality of the prose itself tells us that Benjamin’s relationship to storytelling is far from straightforward. The concision of his stories and his nods to the genre – “It was once upon a time,” one begins – are deceptive. ‘Sketched into Mobile Dust’ for instance tempts us with a simple premise: “in the end, every journey and every adventure must revolve around a woman, or at least a woman’s name.” But the meaning of this premise, like the role of the woman in question, becomes less and less clear. The narrator wanders around town, pursuing tangential urges, until he finds himself in the middle of a street party, staring at a road sign emblazoned with the woman’s name.

The name functions as a recurrent clue – “the red thread of experience,” Benjamin calls it – running through the story. (Benjamin had long-standing plans to write crime fiction.) And the clue signifies something less like narrative than a conspiracy of meaning, in which the protagonist is trapped. At the same time this delicate thread is always at risk of being overwhelmed by the disorientation and melancholic intensity of urban experience. Hence, at the story’s peak, in the midst of the revelry, just before seeing the sign, the narrator asks:

Did nobody notice me, or did this man who was lost to this scorching and singing street – he who I was more and more becoming – appear to everyone to belong here?

“He who I was more and more becoming”: the narrator chances upon himself in the third person, as though misrecognising his own reflection in a passing car. The anonymity of the street is redoubled as it is thrown into question. There is an exquisite awkwardness to this sentence. As with many of Benjamin’s sentences, you have to squint at it, as though through some optical instrument. It twists back on itself, curiously pinched and self-conscious (like Klee’s figures), as if straining to express several things at once.

At times the meanings of words themselves come under peculiar strain. The translators’ job must have posed special difficulties. In one piece we read about a Nordic landscape in which the sun “roars”, the movement of gulls is “unspeakably variable” and large roses are simply “more meaningful”. The language requires nimble, semi-animistic leaps (how can a rose be ‘more meaningful’? Wittgenstein’s grammatical conundrum comes to mind: “the rose has teeth in the mouth of a beast.”) Elsewhere a wall swings through the landscape “like a voice”.

Time and again reading this book, the framing of the stories – their length on the page, titles, opening words – leads you to expect the succinct, gem-like secret of a fairytale, what Benjamin elsewhere calls a story’s “chaste compactness”. But every time, your stomach is left in a knot. The narrative snags on a phrase, a detail, a gesture. Susan Sontag has described Benjamin’s prose style as “freeze-frame baroque”: “This style was torture to execute.” Where does this anguish, this awkwardness, come from?

In the introduction, the editors helpfully situate Benjamin’s stories in the context of his scattered oeuvre. They also include several of Benjamin’s book reviews in the volume, which point to concerns at work in the stories: travel, Berlin, German Romanticism, Italy, folk tradition, childhood. The pleasure of reading the book is something like that of discovering a rare bootleg in a record shop. There are the alternative takes (sections from Berlin Childhood around 1900 and One Way Street); the outtakes (many unpublished in Benjamin’s lifetime); the studio asides (an account of his experience messing up a radio broadcast); new gems, such as the beautifully taut ‘Tales Out of Loneliness’. And like a good bootleg, the collection yields a subtly altered clarity on the wider work.

The title of the book – The Storyteller – is borrowed from a 1936 essay on the Russian author Nikolai Leskov. There we find the first and most obvious explanation of Benjamin’s ambivalence towards the story form. Leskov, for Benjamin, retained a connection to the roots of storytelling in oral tradition, and as such was one of the last of his kind. The argument has more than a trace of medievalism: storytelling belonged, in its origins, to a pre-industrial world of artisans and journeymen. Benjamin pronounces the slow and inevitable death of this tradition in the face of history’s technological-productive forces.

Hence the title of the collection is not without irony. Benjamin was not, by his own account, a born storyteller, because to be such a thing was now impossible. He was a storyteller in spite of himself, in deliberate bad faith, and his stories seem to flinch under his own scrutiny. Their contortions tell us that he was as much concerned with storytelling as with its impossibility.

In the essay on Leskov, Benjamin’s argument has a further stage, canonical to accounts of modernist formal experimentation. If the decline of the oral tradition, on which written stories implicitly depend, had been long coming, then the First World War accelerated it to the point of oblivion:

A generation that had gone to school on a horse-drawn streetcar now stood under the open sky in a countryside in which nothing remained unchanged but the clouds, and beneath these clouds, in a field of force of destructive torrents and explosions, was the tiny, fragile human body.

The very possibility of communication was jeopardised as experience was shattered and wrenched away from any sense of the natural order of things: “men returned from the battlefield grown silent”.

This harrowing argument, by itself, leaves storytelling little room for manoeuvre. And as an explanation of the disquiet underlying Benjamin’s own stories, it is a little too quick of the mark, as it suggests a degree of wretchedness and disintegration that is alien to them. His characters are not – or not obviously – reduced to ‘tiny, fragile’ human bodies: they are not so abject. They are noblemen, bachelors, eccentrics – a New York banker, a baron, Krambacher the “rather dwarfish clerk” – and seem several steps removed from the brutality of industrialisation and war. The ordeals they face are socially and often erotically fraught, but hardly to the point of psychic or physical devastation; their emotions are refined and intensely intimate. A child lies in bed and wonders why the world exists. Günter Moreland drifts despairingly around town, eventually returning to a prostitute, but not before checking his tie in a passing reflection: “it sat well.”

The death throes of storytelling, then, were less acute and more protracted. Their pain manifested as a persistent unease. Devoid of heroism or moralism, Benjamin’s stories are constricted, fitful, sometimes incomplete; the fixtures of the genre – plot, pacing, character – become tenuous. A story, for him, was a device, a time-bomb, always threatening to jam or detonate, but he continued to tinker with it, like a technician trying to defuse an explosive. He becomes, as in one of his dream sequences, ‘the tight-lipped one’, meting out each sentence with a certain trepidation.

And this process is itself constantly fruitful and absorbing. Benjamin’s stories are rich, above all, in details – flowers embroidered on a merchant’s clothes, black veins on a woman’s cheek, bits of word play – which appear suddenly, unaccountably vivid. This may be why his prose was so suited to dreams: they tend to culminate in details. In one, he buys an ingenious toy, fitted with three panels:

I have not forgotten my precious treasure, which more than anything I want to show to everyone. […] The first panel: that colourful street with the two children. The second: a web of fine little cogs, pistons and cylinders, rollers and transmissions, all of wood, whirling together in one plane, without person or noise. And finally the third panel: a view of the new order in Soviet Russia.

The storyteller in Benjamin was related to the antiquarian in him – also to the collector, the miniaturist and the philologist. He was drawn to stories just as he was to pieces of antique debris, automata and pre-cinema optical devices – drawn to them precisely because of their untimeliness.

This was a persistent and complex instinct. Stories, perhaps within living memory, had finally faded into obsolescence. They were ruins fresh on the ground, and with deep foundations. (The angel of history on the opening page looks on.) But these ruins – or their uppermost layers – were recent enough to speak to the present, though now in a half-unintelligible language. And this dislocated language provided an unlikely source of identification and strength, becoming by turns strangely clear-sighted and even prophetic (the new Soviet order mapped out in a wooden toy). Benjamin could have been describing his own method when he said of Kafka’s stories: “He inserted little tricks into them; then he used them as proof ‘that inadequate, even childish measures may also serve to rescue one.’” At the same time his curiosity was always on edge. He felt it as keenly as he felt its insufficiency – and never one without the other. “[A]mbiguity displaces authenticity,” he wrote in One Way Street. In the end, what makes these stories so vital, and what makes it possible to return to them repeatedly, is also what makes them hard to pin down.

Geoff Tibbs is a writer and artist, based in London and Kolkata. Also a practicing magician, he has written on the history of popular entertainment and performance magic. He is co-editor of Different Skies, which publishes new experiments in creative non-fiction, free prose and criticism.

Please support the HKRB by following our Facebook page.