J.R. Osborn talks with Neil Jordan about one of the most notorious nights in the history of literary prize-giving.

In 1979, Dambudzo Marechera and Neil Jordan were awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize. Both writers received the recognition for their first books – Marechera for The House of Hunger (1978, Heinemann); Jordan for Night in Tunisia (1976, The Writers and Readers Cooperative) – and this was the only year in which the Guardian Fiction Prize was awarded to two authors. During the award ceremony, Marechera gave a provocative speech and then preceded to toss furniture around the room. In this interview, Neil Jordan reflects on the event and his memorable interactions with Marechera.[1] Mr. Jordan went on to develop an acclaimed career as a writer and filmmaker, including an Academy Award (Best Original Screenplay) for The Crying Game (1992), a Golden Lion from the Venice International Film Festival for Michael Collins (1996), and a Silver Bear from the Berlin International Film Festival for The Butcher Boy (1997). This is the only interview in which he recounts his experiences with Marechera on the evening of their shared recognition.

J.R. Osborn: In 1979, you shared the Guardian Fiction Prize with Dambudzo Marechera, and that was the only year in which the prize was awarded to two authors. What was your experience of winning the prize?

Neil Jordan: Well, it was it was my first book, and it was Dambudzo’s first book as well. So I flew over to London – I lived in Dublin at the time – and I met with the publishers, and then we went along to the ceremony in one of these grand reception rooms, one of these large theatrical interiors on Drury Lane, and there were these enormous gilt mirrors everywhere.[2] I remember Angela Carter was there. I think she was on the judging committee.[3] I had won for a collection of stories entitled Night in Tunisia and Dambudzo had won for The House of Hunger.

JRO: Was that the first time you had interacted with Dambudzo? Had you met him before?

NJ: No, I’d never met him. I’d never even came across him. His book House of Hunger was published in a branch of a British publishing house that dealt with African literature.[4] He came along with several people, and he gave a little speech, you know.

JRO: Did you both give speeches?

NJ: I gave a speech before he did, I think. The ceremony was all very well-intentioned, and everybody from literary London was there. Everybody had very liberal opinions and they were all quite nice. But I’d never encountered people like this before. And then Dambudzo got up and he made this really – what would you call it – combative speech about how he was being patronized and how he rejected the colonial atmosphere of the prize. He made this extraordinary speech. And the audience were all kind of nodding along, and they were all a bit embarrassed how the English can be – they’re very good at embarrassment, English people. Then he came down off the stage, we both accepted our awards, and we got our photograph taken and all that. And then he began throwing things. He began throwing chairs at huge mirrors, and he began basically to wreck the place. It was the most extraordinary thing. And all of these literary Londoners were going: “Isn’t it wonderful. There’s times you really feel like doing this, but you never really do it, do you?” That’s my memory of it now.

JRO: So, as you remember it, there was, a shift. At the beginning his speech was quite forward and then…

NJ: Yes, his speech was very combative and quite angry, actually.[5] But, you know, it was a cool speech. I really appreciated it, and I understood exactly where he was coming from. Then the chairs began flying around the room. And those in attendance, they were very polite people. They would have let him wreck the whole theatre. They wouldn’t have intervened at all. But he kept on wrecking the place. And either the police or security had to come in eventually. So it’s one of those very unusual events. Marechera arrived with several friends, but we then met later because he had nowhere to stay.

JRO: Was this the same day that you met him?

NJ: Yes. He came back to stay with myself and my wife. We were staying in a friend’s house, in a spare room, and Dambudzo either came back with us or he called me. He definitely had nowhere to stay, and he stayed with us that evening. And he was a real live wire. He was cool. I really enjoyed his company, and I liked being with him. But there was a lot of drink taken, and I remember there was a bottle of whiskey. When I woke up the next morning, Dambudzo was sleeping on the floor. And he woke up too, and I was going to make some breakfast, but he took the bottle of whiskey and he filled the glass with it. And he began drinking it. This must have been 10 o’clock or even earlier in the morning. So he finished the entire bottle of whiskey, and he wandered off into London, and I never saw him again. That was my experience of Dambudzo, apart from reading his book, The House of Hunger, which I read later and really enjoyed.

Oh, yes. That’s right. [Laughs] I almost forgot. He planned to come back with me to Ireland. He thought, at the time, that there was a similar attitude toward the colonial experience in Ireland. But he never did come.

JRO: Were your interactions with him limited to just that one day, for about 24 hours?

NJ: Yes, but some of the things he said stuck with me. I remember Dambudzo saying to me, actually, during our conversation, that even more than British colonial rule and the Rhodesian establishment, that he hated Mugabe even more. I remember thinking that this was very interesting because, at the time, Mugabe was quite a revolutionary figure. I think the new regime had just been established and Zimbabwe had changed its name from Rhodesia to Zimbabwe.[6] So I imagined that there was this moment of freedom in this African country which Dambudzo came from. But no, he felt that he was being followed by Mugabe’s secret police, and he felt that it was dangerous for him to go back to Zimbabwe.[7]

JRO: When he returned to Zimbabwe in 1982, he remained very critical of the new Mugabe administration.

NJ: He was perhaps more critical of Mugabe than he was of the literary establishment that he felt was patronizing him. And maybe he was right. If you look at the subsequent history and the eventual direction of Mugabe, maybe he was right on both counts.

Dambudzo lived in a really complicated world. He really did, even then, and I only spent 24 hours at most with him. He was definitely very turbulent. But, still, he was the most charming guy. He was about my age at the time, and I would have loved to hang around with him more. But the way he was living, I couldn’t have survived very long. I remember him telling these awful stories about his background. Didn’t his father die in a train crash?

JRO: Yes, his father passed away when he was fairly young. But even in the biographies of Marechera’s life, there’s this slippage, I’d say, between his persona as an author and what he’s writing and the biographical facts of what he experienced. His writing isn’t biographical, but it is drawn from very deep personal experience.

NJ: There was a lot of invention about his own life and his own background, wasn’t there?

JRO: At the time, in the moment, when you were interacting with him, was there a similar fluidity between invention of his life and…

NJ: No, no, no. I was simply trying to prevent him from getting arrested. Because he had caused considerable damage in the theatre, he really had. I don’t exactly remember the details, but he needed looking after, really. I mean, he had nowhere to stay. He had caused this fracas. Here we were, standing on the steps, and we were both clutching our awards, and he needed support.

JRO: You were also a new author at the time. A Night in Tunisia was your first book. You had been flown to London for this award. And I suspect that it was probably an honor.

NJ: Yes, it was a big deal to me.

JRO: Then, you witness Dambudzo’s speech and actions at the ceremony. Did that influence or shape the way that you interpreted your own award?

NJ: You know, it was just the most extraordinary experience. I had to admire his extremity, his boldness. I wouldn’t have dared to speak to the literary establishment of London like that and accuse them of patronizing me, even though they probably were. But I wouldn’t have said that. I wouldn’t have even thought it. I was just grateful to get a prize. I couldn’t believe it. They paid my fare to London; they gave me a check of some kind. I was just happy to be given this stuff.

JRO: Did you feel that his boldness landed with the audience? You said that “they were very good at performing embarrassment.”

NJ: All I remember are two facts: on the one hand, nobody tried to stop him. Nobody tried to wrestle him to the ground or preserve the gilt mirrors and all that sort of stuff. And on the other hand, they just starred with this rather British embarrassment. It was quite interesting. We’re talking about liberal Britain, you know, good-hearted left-leaning liberal England. He could have burned the place down and they still would have said: “Well that was rather a wonderful display of…” You know, that kind of thing. But it wasn’t helping, let me put it that way: neither the statements he was making nor his condition nor the oppressions that he was trying to describe in a speech.

But his book, The House of Hunger, was marvelous. I just wish he had built on it. It was full of promise. It was full of imagination. I thought I would see a great career, like Chinua Achebe or somebody like that, coming out of this guy. He could have found a future in London, if he had calmed down a little bit. He could have had a future in British publishing and within the British literary world if he had managed to surmount his own problems, and whatever was driving him onto the street constantly.

JRO: Just to recap, then – you met him at the ceremony and he arrived, as you said, with a number of colleagues, or he had some sort of entourage with him. But then, during the ceremony, they also distance themselves from him, and by the end of the evening…

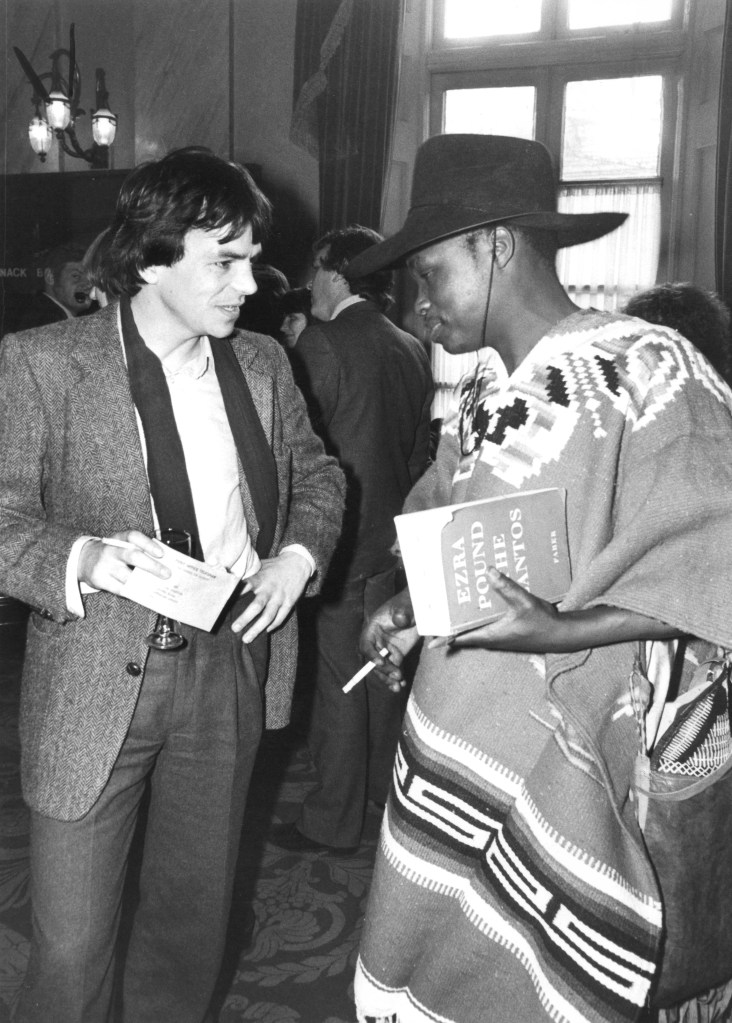

NJ: They just vanished, and I had to kind of look after him. He had nowhere to stay, so I brought him back to the place I was staying. And we had a few drinks and stuff like that, and he woke up in the morning, and he kept on going. That’s my memory of the guy. He was incredibly dynamic, a very beautiful human being, very beautifully dressed with a cowboy hat and a colorful poncho.

JRO: Do you know if this photo was taken before or after the speeches?

NJ: That’s before the chairs began to be thrown.

JRO: And was that evening your only interaction with him?

NJ: In person, yes. Subsequent to that, I began working on movies and a friend of mine, a casting director, was in Harare, and she was casting a movie. Maybe it was for Chris Menges’ film.[8] I don’t remember exactly. But, my friend, she was trying to cast quite a few Zimbabwean people, with real Zimbabweans and not with, you know, black actors from London or whatever. So I said, “Oh, you should meet Dambudzo.” And she did meet with him, I think, but he was homeless at the time and he was in the middle of a long decline.

JRO: After the ceremony, when you left London and returned to Ireland, did anyone follow up with you or ask about the event?

NJ: Oh, no. It was hardly reported upon. I mean, you’re the first person to ask about this. This is the first time that I’ve even heard it mentioned. I’ve described it to people over the years, and they didn’t quite believe me. There was no paper headline: “Writer trashes hallowed British interior” or whatever. There was nothing like that in the papers. It just happened, and people moved on. I don’t remember anything in the papers about it anyway.

JRO: At the time, there wasn’t the kind of constant media sphere that we have now. This is one of the reasons that I was interested in reaching out to you. Some of the literature about Marechera mentions his actions at the Guardian Fiction Prize ceremony. But they are mostly just hints.

NJ: Was there any coverage of the event in the African press?

JRO: There was a little coverage. The Guardian had a brief write-up, but it doesn’t mention any of the damage.[9] And there was a short article in West Africa magazine entitled “Red Faces and Red Wine.” That article is reprinted in a source book on Marechera’s life and works, which I recently acquired.[10] The book contains reader reports on his writings, letters he wrote and received, interviews, school records, and various things.

NJ: Did the report mention the speech and the wreckage?

JRO: The West Africa piece does. That article begins with the word “CRASH” in all caps, and it mentions that a chair was thrown. It’s a thoughtful write-up, but it’s very brief, and, as I said, I just recently discovered it.

NJ: The whole event was so bizarre. It would have been hard even to work out what to say about it. You understand what I mean? … But then, how did you know that he began to smash things up?

JRO: If you read about Marechera’s life, his speech and his actions at the awards ceremony are often mentioned in passing. When I was in Zimbabwe in 1996, I purchased a small tribute book entitled Dambudzo Marechera 1952-1987, which I’ve read and reread again many times over the years.[11] The book ends with a short essay by Flora Veit-Wild, one of the primary biographers and scholars of Marechera’s life, and that essay contains this very intriguing sentence:

“At the ceremony in London at which he was awarded the Guardian Fiction Prize in 1979, [Marechera] hurled cups and plates at the chandeliers, finding the whole affair hypocritical and feeling that no one really understood him.”[12]

NJ: Oh, he threw more than cups, believe me. Maybe my memories are exaggerated, but I don’t think so. And I don’t want to be speaking ill of the guy. But I do remember it was quite a traumatic event. And I do remember there was a mirror or two smashed. Yet still, I remember the guy very fondly. It was very sad to hear of his downward spiral.

JRO: Yes, it was. Thank you for taking the time to share these reflections. And thank you for giving Dambudzo a place to sleep on the night of the Guardian ceremony.

Endnotes

[1] The interview was conducted remotely via video conferencing on September 24, 2020.

[2] The award ceremony was held at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane on November 29, 1979.

[3] The panel of judges for the 1979 Guardian Fiction Prize consisted of Angela Carter, Robert Nye, Norman Shrapnel, Bill Webb, and Christopher Wordsworth.

[4] The House of Hunger was originally published as #207 in Heinemann’s African Writers Series.

[5] Ery Nzaramba wrote and performed a video reenactment of Marechera’s award speech entitled Dambudzo (2010, Maliza Productions, https://vimeo.com/18024234). After watching Nzaramba’s video, Jordan felt that it captured the tone and energy of the speech.

[6] The Lancaster House talks of 1979, which negotiated a ceasefire to the liberation war and the independence of Zimbabwe, were occurring concurrent with the evening in question. The talks concluded on December 15, 1979, 16 days after the Guardian Fiction Prize Award Ceremony.

[7] Marechera’s interactions with the Zimbabwean state apparatus are examined by David Caute in Marechera and the Colonel: A Zimbabwean Writer and Claims of the State (2009, Totterdown Books. Originally published as part of Caute’s The Espionage of the Saints: Two Essays on Silence and the State).

[8] Menges’s film A World Apart was filmed in Zimbabwe and released on June 17, 1988, less than a year after Marechera had passed away.

[9] “Double visions of the imaginative landscape,” The Guardian, November 30, 1979.

[10] Veit-Wild, Flora, ed., Dambudzo Marechera: A Source Book on His Life and Work (2004, Africa World Press). The article “Red Faces and Red Wine,” which was originally published in West Africa on December 10, 1979, appears on pages 188-191.

[11] Veit-Wild, Flora and Ernst Schade, eds., Dambudzo Marechera, 4 June 1952-18 August 1987: Pictures, Poems, Prose, Tributes (1988, Baobab Books).

[12] Ibid., 34. Reprinted from Veit-Wild, Flora, “Words as Bullets: The Writings of Dambudzo Marechera” in Zambezia, 14, 12 (1987): 113-120.

J.R. Osborn is Associate Professor in the Department of Communication, Culture & Technology (CCT) and Co-Director of the Iteration Lab at Georgetown University, USA.