On the publication of her memoir, Emerita Professor of African literatures Flora Veit-Wild shares her memories of the literary firebrand Dambudzo Marechera with HKRB’s Emily Chow-Quesada.

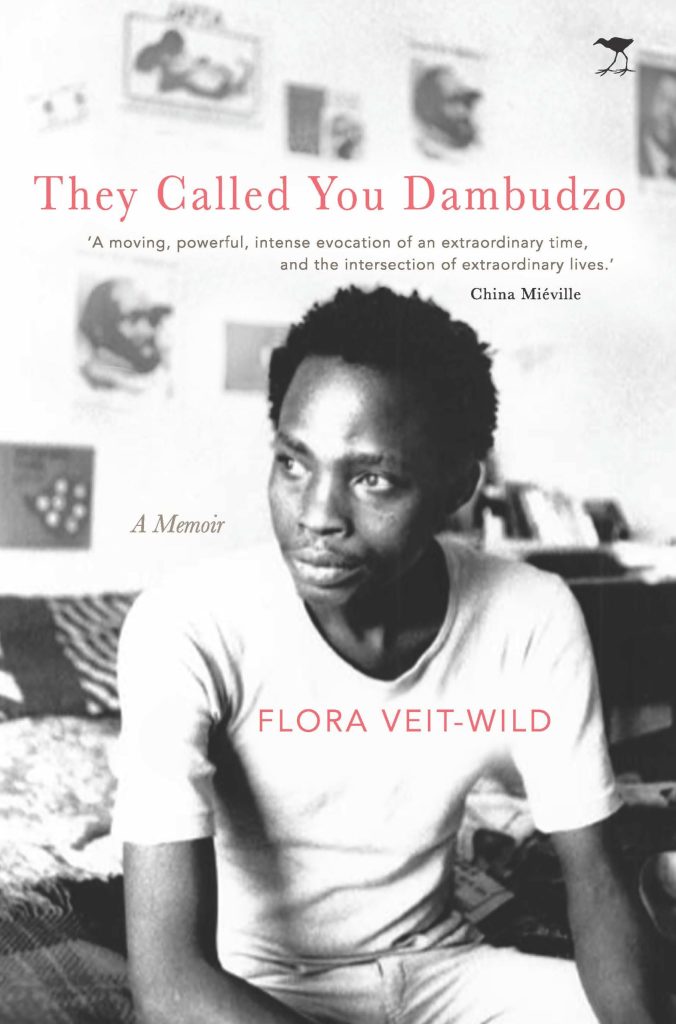

Flora Veit-Wild, They Called You Dambudzo: A Memoir (James Currey, 2022). 300pp.

Emily Chow-Quesada: Dambudzo’s writing has an incredible range – he was a fine poet, novelist, dramatist, and essayist. But for those unfamiliar with his writing, how do you think it best to introduce him? Is Dambudzo’s soubriquet of the enfant terrible of African literature a deserved one?

Flora Veit-Wild: His fame and name as the enfant terrible of African literature relates back to the time when he appeared on the international stage and was throwing “cups and saucers at chandeliers”, in the literal and the metaphorical sense. He did so in 1979 at a prize-giving ceremony, when he received, together with the Irish writer Neil Jordan, the Guardian Fiction Prize. This action expressed his resentment of being patronised by Western literati, his rejection of being classified and categorized as an “African writer”. His appearance in a kind of Latin American outfit and with a thick volume of Ezra Pound under his arm underlined his stance. And so did his writing. While everyone at the time was hailing African nationalism, he was undermining any glorification of Africanness; he turned heroes, sanctities, authorities of all sorts upside down as well as all given standards of writing, creating his own genres, mixing prose, poetry, drama and essay. As many critics have said, he was far ahead of his time and created a literary idiom familiar in postmodernist writing but alien in the nationalist euphoria of the 1980s. How to introduce him? His whole being and writing was explosive, mindblasting, blasphemic, he was a magician of words and images.

ECQ: Your memoir is a special piece of writing in its own right. Why did you decide to adopt this particular way of writing for this particular project?

FVW: It was not a project. I felt the need to capture the unique story brought about by my encounter with Dambudzo Marechera. In my memory, the story was linked to images, scenes, phrases that stuck in my mind; which then had to be put into words, sometimes fed with diary entries, letters, notes and photographs.

ECQ: Memory is a profoundly enigmatic phenomenon – vital yet also always delicate and ephemeral. How do you think a writer should engage with his/her memory in a memoir?

FVW: I hesitate to give advice. I imagine this process is different for each individual. The first steps I think should always be a kind of free writing – let images, scents, objects, scenery, persons pop up in your mind and jot down what they evoke in you. The rest will come by itself. Do not try to follow a specific scheme or structure. That comes later.

ECQ: Your memoir is at times difficult to read because of the raw emotion that it captures. How important do you think it is to offer this emotion to your reader?

FVW: I don’t think it is good to offer “raw emotion” to the reader, and I am surprised that you feel like this. I was writing the story about 25 to 30 years after the events had taken place. I found it at times difficult to recapture the emotion of the moment. And I also tried to avoid becoming melodramatic. Joan Didion’s memoir A Year of Magical Thinking had impressed me in that regard. How to put very emotional moments of your life into “unemotional” prose. One of the most difficult parts, for instance, was to talk about my HIV infection and everything related to it. Here I chose a narrative technique which helped me to shield off the personal anguish: I listed, in a very matter-of-fact, neutral voice, facts which reflected the “Great Scare”, as the pandemic was called, the waves of mass hysteria that were sweeping through the tabloids in Germany and the UK in early 1987, the time I (and my husband) were diagnosed HIV positive. If you still feel “raw emotion”, I hope it means that despite such techniques, or possibly, through these techniques, emotions were created in the reader beyond the words I used.

ECQ: It certainly was for me! Thank you for your time today. It has been a pleasure.

Emily Chow-Quesada researches on world literature, postcolonial literature, and representations of Africa in Hong Kong. She has published journal articles and book chapters on Anglophone African literature and representation of African cultures. Her current project looks into the representations of blackness in Hong Kong media. She has taught courses in world literature, postcolonial literature, African literature, representations of blackness, and cultural studies.