Paul Scott Stanfield reviews a new collection of poetry from the award-winning poet Brenda Shaughnessy.

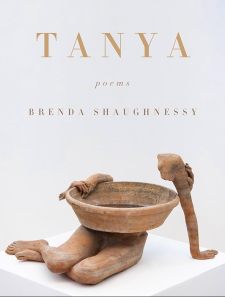

Brenda Shaughnessy, Tanya (Knopf, 2023), 112pp.

Anyone reviewing Brenda Shaughnessy’s new book Tanya carries the burden of knowing that Shaughnessy is on to them. In “Tanya,” the book’s long closing poem, Shaughnessy considers those “who buy and sell books” and those who “ignore, forget, rave, quote”—who review them, in effect, as part of the general traffic of publishing. For the writer, “your book is you,” but for the reviewer, “your book is you, but theirs.”

You see? They love the you

That is theirs (your book)

And so they

position you

for special experiences

where you have a mic or are in Biz Class

Or a room full of people

With your book on their lap and flowers.

And it’s true. As a reviewer, or simply as a reader, when I love a writer’s book, I love the book that is mine, the book about which I can say well-informed and discerning things, the book I can recommend or celebrate, the book I can shelve in a conspicuous place to make my sensibility visible. Brenda Shaughnessy is on to me.

Calling “Tanya” a philosophical poem would raise misleading expectations, but it has certain affinities with the later Wittgenstein, the writer of Philosophical Investigations and On Certainty. Wittgenstein called these books “remarks” in which “there is sometimes a fairly long chain about the same subject, while I sometimes make a sudden change, jumping from one topic to another […]”. The remarks typically concern something commonplace, even unremarkable—a spoken request for building slabs, a tree in the yard—yet see the familiar thing from an oblique point of view, rendering it unfamiliar, even bewildering, though in a fruitful way. “Tanya” has a form (twelve sections with a varying number of six-line stanzas that proceed across the page like a descending staircase) but always feels more improvised than programmed, like a long walk that turns out to be less about its destination than about what one encounters along the way. What we encounter is, as in Wittgenstein, often commonplace or familiar—publishing books, for instance, or rearing children—but seen from a different place, revealing unfamiliar aspects.

Parents of grown children

tell me grown children

Leave but you can’t touch their rooms.

And you can’t leave.

You have to stay there for when they come back,

Like you’re a paused video but they forget

To watch you when they come back.

Or they don’t come back

So you’re like the mom in The Leftovers

Doing chores for nobody.

Susceptible to taking tangents though “Tanya” is, its orbits do have a center. It is addressed to Shaughnessy’s roommate from her first year in college, a person she has not kept in touch with but who has circulated in her imagination ever since. One’s first year in college is often an era unto itself, and the relationships that defined that era are indelible in memory even if they turn out to be brief: “You know I’ve been wanting to write / about you for over thirty years.”

You probably guessed I’d hide you here,

in a long, careening poem, making you

as hard to find as you are.

I waited until you were really gone

but I think you are not dead,

just gone to me.

Shaughnessy suggests it was Tanya who definitively ended the friendship: “What did I do to you make you leave me / as if you hated me?” Perhaps Shaughnessy was “fatherly,” that being “the only thing anyone could do / that you found unforgivable.”

Shaughnessy’s years-later consideration of the first-year-roommates dyad in “Tanya” continues her long interest in the dynamics of small collectivities, such as her middle school circle of friends in “Is There Something I Should Know?” from So Much Synth, her partner and children in her previous book, The Octopus Museum, or the lovers in her first book, Interior with Sudden Joy. Distinctive though Shaughnessy’s voice always is, it consistently bears witness to the idea that we are in great part whom we live with. Tanya as a whole volume bears further witness to that idea in its tributes to female mentorship: both direct, in “Coursework,” a longer poem about Shaughnessy’s teachers that forms Part II of the volume, and mediated, in a sequence of poem about women artists that forms Part I. Working with an expansive notion of the ekphrastic tradition something like that of Mary Hickman in Rayfish, Shaughnessy sets before us Meret Oppenheim’s fur-covered cup and saucer, Lauren Lovette’s choreography, Torkwase Dyson’s multimedia work, Ursula von Rydingsvard’s sculpture, and Jessica Raskin’s paintings, among others. In these poems, too, Shaughnessy writes with an abiding sense of the self’s involvement in the mystery of the other: “We know there’s something beyond our shadow triangulating to trick us into thinking / we are complete, formed, solid. We know there’s something beyond it / even if all we know is that we know.” As if to emphasize the point, Part I begins and ends with poems to a not quite identifiable “you,” as if our individuality is always already dyadic.

The language of Tanya has a signature move, the placement next to each other of words with distinct meanings and etymological histories that happen to be partly or entirely homophonic:

It’s no solution to our probable problem

(“Moving Far Away”)

The tub the cup the jug

the mug many things

with U in it.

(“Tell Our Mothers We Tell Ourselves the Story We Believe Is Ours”)

my surfaces servicing

(“The Impossible Lesbian Love Object(s)”)

A dress is not an address, where you live,

A dress is addressed to you, yes,

Assigned to you, but not a sign you’re you.

(“On The Shaded Line by Lauren Lovette)

We meet again.

We: meat, again?

(“On Romeu, “My Deer” by Berlinde De Bruyckere”)

Ours, ours.

Hours and hours.

(“Tanya”)

As in a well-found rhyme, placing the words side by side lends accidental similarities of sound an uncanny shimmer of design, as if the key to some code has been discovered. So, too, it may happen, with freshman year roommates: an arbitrary decision in the housing office may be the keynote of the beginning of your adult life. So it may be even with our families, “the accident of love I was born into,” in Shaughnessy’s phrase, in which the tumbling dice of DNA are aleatory when seen from one angle, destiny when seen from another.

Now six books along in an ever more interesting career, Brenda Shaughnessy has once again shown a gift for reconciling contraries. In her earlier work, playfulness has danced a pas de deux with earnestness, candid transparency with a smoky mysteriousness. Here, in Tanya, we are led to ask, what is accident, what is design? Can we really tell them apart?

Paul Scott Stanfield was educated at Grinnell College and Northwestern University, and is recently retired from the English Department of Nebraska Wesleyan University. He is the author of Yeats and Politics in the 1930s and of articles on Yeats, other Irish poets, and Wyndham Lewis.

Find us on Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/hkreviewofbooks/

You must be logged in to post a comment.